What is a Safe Withdrawal Rate for Retirement?

Jay Abolofia, PhD, CFP® is a fee-only, fiduciary & independent financial planner in Waltham, MA serving clients in Greater Boston, New England & throughout the country. Lyon Financial Planning provides advice-only comprehensive financial planning for a flat fee to help clients in all financial situations.

We spend much of our early years accumulating assets that we later decumulate to fund liabilities in retirement. So, what is an ideal strategy to draw down these assets in retirement? Is one approach “safer” than another? In what follows, I analyze conventional retirement distribution strategies, including the well-known 4 percent rule, and contrast them with an economics-based approach.

Conventional retirement distribution strategies

In drawing down your savings in retirement, conventional planning recommends you select a fixed withdrawal strategy. These strategies assume you draw a fixed percentage (e.g., 4%) of your initial retirement savings each year, adjusted for inflation, throughout retirement, independent of how your investments perform. For example, if you start retirement with $1M, you will draw $40,000 in the first year and increase that draw every year with inflation.

First Year Draw ($) = 4% x Prior Year’s Savings ($)

Subsequent Year’s Draw ($) = Prior Year’s Draw ($) x (1 + Inflation (%))

Fixed withdrawal strategies originated from research by William Bengen in 1994 and three finance professors from Trinity University in 1998. By analyzing US stock and bond returns from 1926 to 1995, these researchers identified the historical success (or supposed “safety”) of different fixed withdrawal strategies. They found that drawing a fixed 4% from one’s initial retirement savings each year, with annual inflation adjustments, over a 30-year time horizon resulted in less than a 5% chance of running out of money.[1] This finding is what ultimately led to the so-called 4 percent rule.

The trouble with the 4 percent rule

Distributing a fixed percentage from your initial retirement savings each year seems straightforward, intuitive and practical. The research behind the approach is well-known and accurate, and most advisors deem the approach “safe”. So, what’s not to like? Here are three major issues.

The success of any fixed distribution strategy, by definition, can only be known in hindsight. Identifying what fixed strategy worked over some historical period, tells us little about the effectiveness of that strategy going forward.

Given that your investments fluctuate in value, any fixed distribution strategy will maximize sequence of return risk. The greater the variability in your investment returns, the greater the risk that a fixed withdrawal strategy will result in running out of money or leaving an unspent surplus.

Any nonzero probability of running out of money in retirement is unsafe. Choosing a fixed withdrawal strategy or investment allocation in retirement based on an arbitrary probability of success is dangerous.

The dangers of the 4 percent rule become extraordinarily clear when you examine different possible trajectories for your retirement savings. Imagine you draw $40,000 a year, adjusted for inflation, from an initial savings of $1M. What happens to your savings over time depends on the magnitude and sequence of investment returns you experience, which are out of your control.[2] For example, Figure 1 illustrates a series of relatively poor investment returns, whereby taking distributions according to the 4 percent rule (gray line) results in running out of money by age 86 (blue line). On the other hand, Figure 2 illustrates a series of relatively good returns, resulting in an unspent surplus of $227,534 at age 95.

This exercise highlights that employing an inflexible spending strategy puts your retirement plan at risk. On the one hand, you may run out of money, having to rely solely on guaranteed income, like Social Security, later in retirement (Figure 1). On the other hand, you may underspend in retirement, leaving a surplus to your heirs that you otherwise didn’t plan to (Figure 2). Being a financial burden to others is certainly worse than leaving a bequest, but neither are ideal.

Figure 1. Employing a fixed distribution strategy when investment returns are naturally variable, puts you at risk of running out of money.

Figure 2. Employing a fixed distribution strategy when investment returns are naturally variable, puts you at risk of leaving an unspent surplus.

An economics-based retirement distribution strategy

In contrast to the conventional approach, economics-based planning recommends employing a dynamic retirement distribution strategy. By taking into account that investment returns are naturally variable, this approach adjusts your draw each year in order to mitigate the risks of running out of money or leaving an unspent surplus. Rather than drawing a set amount based on a fixed percentage of your initial savings (e.g., 4%), the amount you draw each year will depend on your age, health and level of savings.[3][4]

The idea is to draw a percentage from your retirement savings each year equal to 1 divided by the number of years until your maximum age.[5] If you’re 65 and based on your current health expect that you may live to 95, then you will draw 3.33% from your savings this year (i.e., 1/30). Next year at age 66, assuming you expect the same maximum age, you will draw 3.45% (i.e., 1/29), etc.

Current Year Draw ($) = Prior Year’s Savings ($) x (1/(Maximum Age - Current Age))

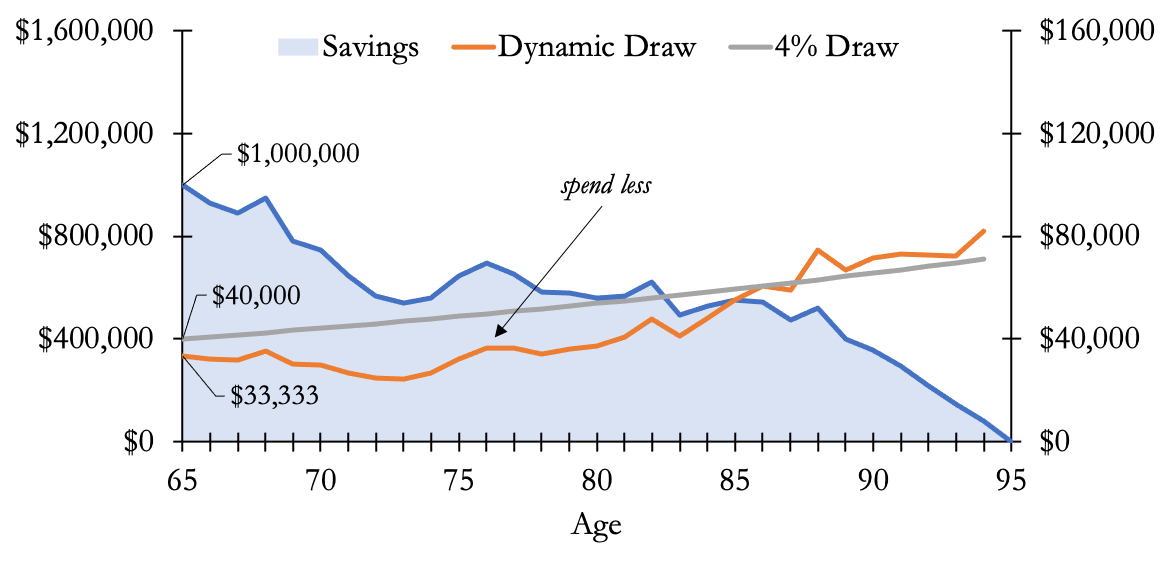

Figure 1A and 2A illustrate this dynamic withdrawal strategy (orange line), assuming the same sequence of investment returns used in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. For example, if your returns are relatively poor, especially early in retirement, then this strategy will advise you to spend less so you don’t run out of money (Figure 1A). If your investment returns are relatively good, then this strategy will advise you to spend more so you don’t leave an unspent surplus (Figure 2A).

Figure 1A. If investment returns are generally poor, as in Figure 1, a dynamic withdrawal strategy will have you spend less along the way, helping you avoid the risk of running out of money.

Figure 2A. If investment returns are generally good, as in Figure 2, a dynamic withdrawal strategy will have you spend more along the way, helping you avoid the risk of leaving an unspent surplus.

Don’t put your retirement spending on autopilot

Although fixed withdrawal strategies like the 4 percent rule are attractive in their simplicity, they fail nearly every financial criterion imaginable. Since investment returns are naturally variable, sticking to a fixed withdrawal strategy, especially early in retirement, maximizes your risk of financial ruin. A series of poor investment returns can easily put your retirement at risk if you’re unable, or unwilling, to reduce your spending as you age.

A more practical approach is to adopt a straightforward dynamic withdrawal strategy determined by your age, health and level of savings. For example, if you expect to live a maximum of 30 more years, draw 3.33% this year (i.e., 1/30) and adjust your draw in subsequent years accordingly. By adapting your retirement spending in this way, you can simultaneously mitigate the risks of running out of money and leaving an unspent surplus.

Footnotes

[1] In effect, historically over that time, a balanced US portfolio of 50% large-cap stocks and 50% intermediate term Treasury bonds had a 95% chance of lasting for 30-years assuming annual withdrawals equal to 4% of the initial savings, with annual increases for inflation. Subsequent research by Wade Pfau incorporating historical returns on equivalent foreign stocks and bonds yielded dramatically lower “safe” withdrawal rates.

[2] To illustrate the variability of investment returns, I utilize a normal probability distribution with a mean nominal return of 6% and standard deviation of 10%. This is representative of a balanced portfolio of about 50% stocks and 50% bonds. I assume a fixed annual inflation rate of 2% for all simulations.

[3] This approach is very similar to the IRS requirement minimum distribution (RMD) rules. However, instead of updating the annual distribution amount based on a predetermined life expectancy table, this approach updates based on an individual’s expectation of their own maximum age, which depends on their current age and health status.

[4] Technically, the economics-based approach also updates the distribution amount each year based on one’s expectations of future real investment returns (r). For example, if you think your investment returns will be greater than inflation going forward (i.e., r > 0), then you can plan to spend slightly more aggressively now and more conservatively later, and vice versa. I remove this complexity here by assuming that one’s expectations of future investment returns are equal to inflation each year. For all my nerdy readers, here is the complete formula. Note that this just an annuity calculation, akin to using the payment function (PMT) on your finance calculator or in excel.

[5] No one has an expiration date, so planning to live to your life expectancy is unsafe. Remember, 50% of people will live beyond their life expectancy. Instead, use a longevity calculator to estimate your maximum age based on your current age and health status. For example, if you currently have a 5% chance of living to 95, then that’s a good starting point. Each year or so in retirement, you can update the estimate based on new data.