Should You Contribute to Traditional Or Roth Accounts?

Jay Abolofia, PhD, CFP® is a fee-only, fiduciary & independent financial planner in Waltham, MA serving clients in Greater Boston, New England & throughout the country. Lyon Financial Planning provides advice-only comprehensive financial planning for a flat fee to help clients in all financial situations.

Saving enough money to maintain your living standard throughout retirement is the most critical step to your financial plan. Also important is figuring out where to save each dollar. This often starts by making contributions to tax-advantaged retirement accounts, including IRAs and employer-sponsored retirement plans, like your 401K or 403B. These accounts have special rules, including when you have to pay taxes to Uncle Sam. In this article, I explore the important question of whether those contributions should be made to Traditional or Roth accounts. As it turns out, conventional wisdom often discounts the benefit of Roth accounts.

Pay now or pay later

Tax-advantaged retirement accounts typically come in two flavors, Traditional or Roth. Both provide tax-deferred accumulation, such that investment earnings grow tax-free within the account. The key difference is that with Roth accounts you pay income taxes on the way in (i.e., on contributions), while with Traditional accounts you pay income taxes on the way out (i.e., on distributions) (see Figure 1 below).[1]

Figure 1. Income tax treatment for Traditional vs Roth accounts

Deciding whether to contribute to a Traditional or Roth account therefore involves comparing the benefits of making a pre-tax (i.e., tax deductible) contribution vs an after-tax (i.e., non-deductible) contribution.[2,3] This requires making an adjustment for taxes. For example, it is not fair to compare the benefits of making a $20,500 contribution to a Traditional account to an equivalent $20,500 contribution to a Roth account—Uncle Sam still owns a portion of your Traditional contribution. An apples-to-apples comparison involves using the following formula:

(After-Tax $) = (Pre-Tax $) x (1 – Tax Rate %)

For example, if you expect your post-retirement tax rate to be 30%, you must compare the benefits of making a $20,500 pre-tax contribution to a Traditional account to a $14,350 after-tax contribution to a Roth account ($20,500 x (1 – 30%) = $14,350).

Consider your tax rate now vs in retirement

Conceptually, you should contribute to the account that yields the greatest after-tax benefit in retirement. Conventional wisdom says the decision depends entirely on your current vs post-retirement income tax rate. Figure 2 below illustrates this simple decision rule (orange line). In short, if you expect your post-retirement tax rate to be higher than it is now (orange area), you should contribute to a Roth account, and vice-versa.

There are several reasons why you may expect your post-retirement tax rate to be higher than it is now, and vice-versa. For example, maybe your current taxable income is relatively low because you are young, taking time off from work, or otherwise earning less relative to what you expect to earn in the future. Or, maybe you are several years older and in poorer health than your spouse, meaning your survivor may pay income taxes at the higher single individual rates.

Figure 2. Conventional wisdom says to contribute to Roth accounts if your post-retirement income tax rate is going to be higher than it is now.

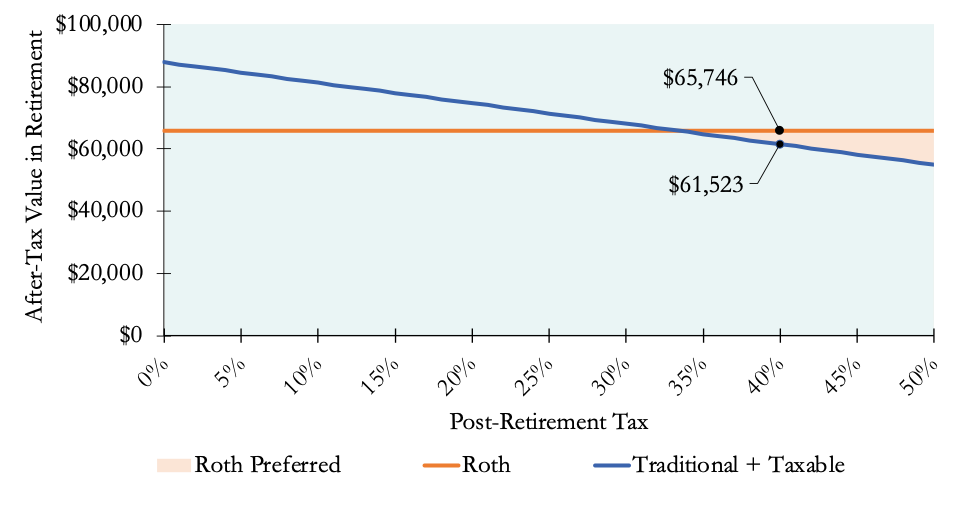

This approach is attractive in its simplicity, but is true only part of the time. Specifically, if you can save more than pre-tax IRS limits (e.g., by maxing out tax-advantaged retirement accounts and investing any excess in a taxable brokerage account), Roth contributions become relatively more attractive. Figure 3 below illustrates how the simple decision rule shifts downward on the graph (orange line) when cumulative retirement savings exceed pre-tax IRS contribution limits. This increases the range of post-retirement tax rates for which Roth contributions are preferred (orange area).

Figure 3. If you plan to save more than pre-tax IRS limits, Roth contributions become relatively more attractive than conventional wisdom implies. How much more attractive, will depend on your situation.

Note: The decision rule shown here is but one example. Yours will depend on the factors below.[4]

In other words, even if you expect your tax rate to fall in retirement, contributing to a Roth rather than Traditional account can still make sense when your overall savings is high. The reason is because using the Roth rather than Traditional account allows you to get tax-deferral on more dollars.[5] For instance, in the example above, making the correct decision to contribute to a Roth account when conventional wisdom says otherwise can save you up to $4,223 over 20 years, equivalent to an increase in your after-tax annualized return of 0.35%—not bad for a one-time, seemingly trivial, decision.[6]

If you’re saving a lot, consider these additional factors

As Figure 3 illustrates, when saving more than pre-tax IRS limits, the decision rule (orange line) depends on more than just your current vs post-retirement income tax rate. It also depends on:

How much you save relative to contribution limits on tax-advantaged accounts

How long you invest the money

The tax rate on capital gains distributions and stock dividends

Whether you plan to invest more in stocks or bonds

The expected interest rate on bonds

The expected dividend and capital appreciation rates on stocks

So, if you find yourself maxing out tax-advantaged retirement contributions and saving more to a taxable account(s), you’ll want to consider how changes in the above factors may impact your decision rule. As you can imagine, the math is tricky (see my video and spreadsheet below)! Nevertheless, here is a summary.

If you are saving more than pre-tax contribution limits in your tax-advantaged accounts, Roth contributions become relatively more attractive, and vice-versa

If you plan to invest the money for a longer period of time

If your current or future capital gains tax rate goes up

If you plan to invest more of your savings in bonds than stocks[7]

If you expect bond interest rates, stock dividend rates and/or stock appreciation rates to go up[8]

When in doubt, make a plan

Conceptually, the decision to contribute to Traditional or Roth accounts depends on comparing your current vs post-retirement income tax rates.[9] If you expect your tax rate in retirement to be equal to or higher than your current rate, contribute to Roth accounts. If you’re unsure, you’ll want to do more analysis. For example, if you are maxing out tax-advantaged retirement accounts, Roth contributions become relatively more attractive than conventional wisdom implies—especially if you plan to invest the money for a long time.

Practically, however, forecasting your post-retirement tax rate can be difficult and involve long-term planning. For instance, how much do you expect to earn and when will you retire? How much will you contribute to Social Security? How much do you expect to spend on housing, taxes, consumption, and other goals? At some point, you may want to stop guessing and start planning!

See My Video & Spreadsheet to Calculate Your Own Decision Rule!

Appendix

Figure A. If your current and post-retirement tax rates are 40%, conventional wisdom says Traditional or Roth contributions will lead to the same after-tax value in retirement. If you’re saving more than pre-tax IRS limits, however, conventional wisdom is incorrect. Making a Roth contribution instead can save you $4,223 over 20 years ($65,746 - $61,523).

Note: See footnote [4] for specific inputs used in this example.

Footnotes

[1] IRS contribution limits to employer-sponsored retirement plans are typically higher than IRAs and unrestricted based on income. Whether and how much you can contribute to an IRA may depend on your age, income, tax filing status and whether you or your spouse has an employer-sponsored retirement plan.

[2] Note that the decision to do Roth conversions (i.e., pay income taxes now to move assets from Traditional to Roth accounts) involves a similar calculus. This strategy goes beyond the scope of this article.

[3] Technically, some employer-sponsored retirement plans allow for after-tax contributions in addition to Traditional and Roth contributions. These nondeductible contributions grow tax-deferred until retirement, unless they are immediately rolled over to Roth, in which case they grow tax-free. This strategy, called a mega backdoor Roth, goes beyond the scope of this article.

[4] The decision rule shown here (orange line) assumes the following: total after-tax savings equals IRS limits (i.e., enough to max out Roth contributions), 20-year time horizon, 15% tax on capital gains distributions and stock dividends, half of all savings is invested in stocks and half in bonds, 4% bond interest, 2% stock dividend, and 6% stock appreciation.

[5] Recall from our earlier example that contributing $20,500 pre-tax to a Traditional account is equivalent to contributing $14,350 after-tax to a Roth account. Thus, if you have additional savings, putting those dollars first into a Roth account is clearly preferred to putting them first into a taxable brokerage account.

[6] This assumes total after-tax savings equals IRS limits and that current AND post-retirement tax rates are 40%. The dollar amount is the difference in after-tax value in retirement of contributing to the Roth vs Traditional. The annualized return is the difference in compound annual growth rates (CAGR) over 20 years. See my video and spreadsheet for details.

[7] If your overall asset allocation favors bonds over stocks, Roth contributions become relatively more attractive. This is because you’d rather have (tax-inefficient) bonds in a tax-free Roth account than a taxable brokerage account, where bond interest may be taxable at ordinary income rates.

[8] In general, you’d prefer your investments (whether stocks or bonds) to be in Roth accounts, where income and appreciation is tax-free, rather than in taxable accounts, where income and appreciation is taxable. And the better performing are those investments, the better off you are having them in Roth accounts.

[9] Note that Roth accounts also have ancillary benefits that go beyond the scope of this article, including tax- and penalty-free withdrawal of contributions before retirement, no required minimum distributions in retirement, and income tax-free transfer to heirs. Roth distributions in retirement are also not considered income by the IRS, meaning they may help to reduce Medicare Part B premiums and taxes on Social Security benefits.