The Cost of Children

Jay Abolofia, PhD, CFP® is a fee-only, fiduciary & independent financial planner in Waltham, MA serving clients in Greater Boston, New England & throughout the country. Lyon Financial Planning provides advice-only comprehensive financial planning for a flat fee to help clients in all financial situations.

Children are expensive. Between housing, food, childcare, enrichment and education, the expenses add up fast. The USDA estimates that raising a child through age 17 can cost about $250-500K for middle- to high-income families in the United States. Including any foregone earnings, college and ongoing expenses can increase this number considerably. In what follows, I breakdown the various financial impacts that children can have on your financial plan, focusing primarily on your household’s living standard.

Plan on Spending More and Saving Less While Your Child is Dependent

A household with children will certainly have more expenses than one without, and thus be capable of supporting a lower living standard, all else equal. With one more mouth to feed, there’s simply fewer resources to go around. Not only do children lower a household’s living standard (or per-adult discretionary spending), they also dramatically alter the pattern of household spending over time.

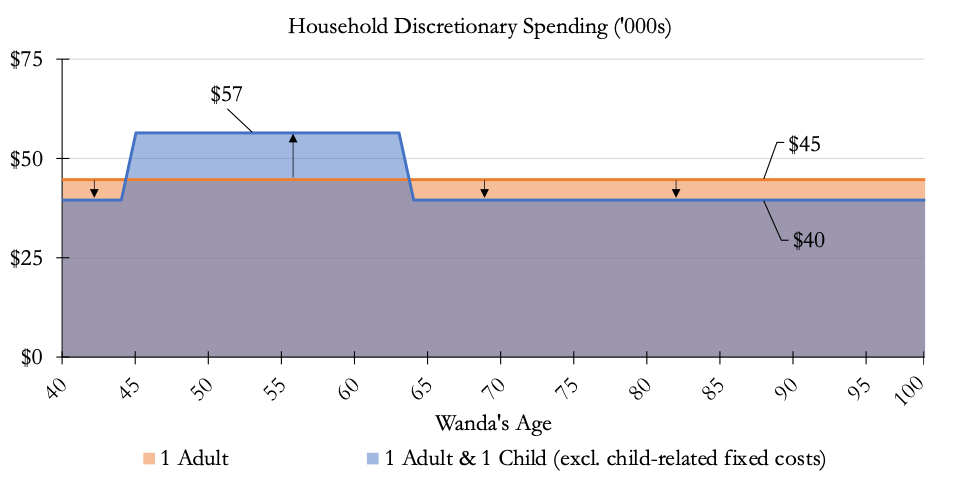

Let’s reconsider the hypothetical case of Wanda Worker, a single person with no dependents. Her lifetime balance sheet estimates that she can afford to spend up to $45K per year on discretionary spending (e.g., food, clothing, travel, leisure, entertainment) after covering all her committed expenses (i.e., taxes, housing, insurance and personal goals). In other words, without children, Wanda can cover all her fixed costs and spend up to $45K per year to support her living standard through age 100 (orange line in Figure 1).

Your lifetime balance sheet is a key component of economics-based financial planning, rooted in the idea that you can’t spend more over your lifetime than you have in financial resources. This approach is distinct from conventional financial planning, which has no such framework.

Now, consider what happens if Wanda plans on having a child in 5 years. For now, let’s exclude any and all child-related committed expenses, including any increases in housing, childcare, enrichment and education spending. In this simplified case, if the only thing that changes to Wanda’s plan is having a child, her lifetime balance sheet remains exactly the same. With no changes to her lifetime assets or committed expenses, over the next 60 years, she’ll still have $2.7M to spend on household discretionary spending. However, because she expects to have one more mouth to feed, the pattern of that spending will change over time (blue line in Figure 1).[1] Rather than being able to afford a flat $45K per year, her discretionary spending will fluctuate with the dependence of her child.[2] For example, she can now afford to spend $57K per year on discretionary spending while the child is dependent and $40K per year otherwise.[3]

This highlights an important factor about having children. Even without considering the additional fixed costs involved in raising a child, you’ll be forced to spend more as a household while the child is dependent and less in the years before and after, including in retirement. Having more mouths to feed, even if only for about 18 years of your life, means you’ll need to save more and spend less in the years before and after your child is dependent. This pattern is what allows your household to afford the increased spending and reduced savings that typically occurs while your child is dependent.

Figure 1. Having a child means spending more, and therefore saving less, while the child is dependent.

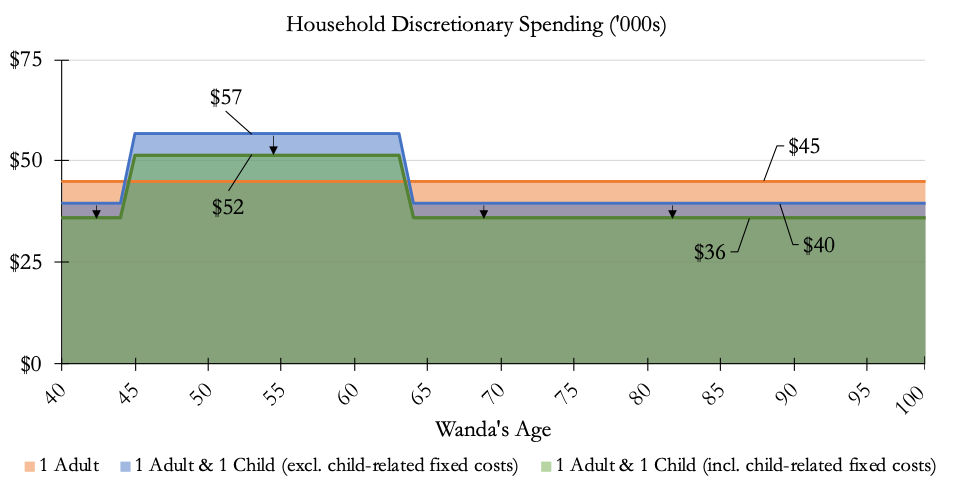

Spending More on Your Child May Further Reduce Your Living Standard in Retirement

Now, let’s consider what happens if Wanda plans to budget for additional child-related committed expenses, like $10K per year for childcare (ages 0-5), $5K per year for enrichment (ages 6-18), and $30K per year for college (ages 19-22). Adding in these extra lifetime expenses of $245K changes Wanda’s lifetime balance sheet by directly reducing the amount of resources she has available to spend on household discretionary spending over her lifetime.[4] With these added fixed expenses, Wanda’s affordable household discretionary spending now falls in every year of life (green line in Figure 2). For example, she can now afford to spend $52K per year on discretionary spending while the child is dependent and $36K per year otherwise.[5]

This highlights another important factor about having children. The more you spend on fixed child-related expenses, like child-care, enrichment, college, and increased housing costs, the more you will need to save and less you can afford to spend on discretionary spending throughout your life, including in retirement. In other words, one more dollar spent on your child now is one less you’ll have set aside for spending on something else in the future.

Figure 2. Fixed expenses, like child-care and education, further reduce how much you can afford to spend on discretionary expenses throughout your life.

Turn That Frown Upside Down

Few parents need to be reminded that their children are expensive. With more mouths to feed, there’s simply fewer resources to go around. Plus, any additional child-related fixed expenses can further tighten your household’s cash flow. Economics-based financial planning reminds us that having dependents fundamentally changes the pattern of discretionary spending over time. In order to support your household’s increased spending and reduced savings while your child is dependent, you’ll need to save more and spend less in the years before and after. Failing to do so, could mean having to reduce your living standard in retirement or relying on family support as you age. But to end on a high note, recent research suggests that having children can increase parents’ happiness when controlling for financial difficulties. In other words, a sound financial plan can turn a parent’s frown upside down :-)

Footnotes

[1] Having more than one child will further alter the pattern of household discretionary spending over time. With each additional child, household discretionary spending increases while the child is dependent and decreases thereafter, creating a staircase pattern. The size of each change will depend on key family economics assumptions, including the economies of shared living and the relative cost of children to adults.

[2] However, whether she has a child or not, her living standard (or per-adult discretionary spending) remains smooth at $45K per year without a child and $40K with. This idea of “consumption smoothing” is another key component of economics-based financial planning.

[3] For all those mathematicians out there, the area under the orange and blue curves in Figure 1 are both equal to $2.7M.

[4] For simplicity, I continue to disregard any tax implications of having children and assume a real interest/discount rate of 0% ($10K x 6 years + $5K x 13 years + $30K x 4 years = $245K).

[5] For all those mathematicians out there, the area under the green curve is $245K less than the area under the blue and orange curves in Figure 2 ($2.7M - $245K = $2.455M).